Of course, it makes sense that the city would maintain large historical landmarks, but even the more quaint and unobtrusive structures are preserved if someone can find a use for them. It's not uncommon to be walking down the street and see large, modern, aluminum alloy shopping complexes next to old shops with wooden foundations and stone masonry long since turned brackish by run-off and acid rain. The area around the college campus is rather modern looking, but going into the city center is like stepping into another time. The roads are entirely cobblestone and vendors sell jewelry, food, and old books with fraying leather spines on the street. The roads were clearly designed for walking. They dip and wind in unpredictable, irrational directions, and frequently I see drivers have to stop and turn around when a road abruptly becomes accessible only to pedestrians.

This contrast is even more apparent in Beune, a small city about five miles outside of Dijon which I visited on Tuesday of this week.. The largest main historical landmark in Beune is L’Hôtel Dieu (God’s hospital). Constructed by Nicolas Rolin, a priest and chancellor to Phillip the Good in 1443, the hospital was built as a refuge for impoverished sick people. The building has a distinct aesthetic in and of itself. The main room's ceiling is built to look like the bilge of a boat, and the wood is carved to resemble the faces of men and animals, each of which represents some sort of trait or character flaw. Every face is unique, and the animal carved next to it correlates with that person's sin. A pig, for example, represents lust. Inspired by Noah's arc, the ceiling was meant to bring joy to the sick people, many of whom would die in their beds, with some form of entertainment and hope of renewal.

|

| The ceiling in the main room. |

The chapel at the end of the hall stands underneath an immense strained glass window. In addition, the walls are painted red and inscribed with the word "seule" (alone) in golden letters. Diagonal to the word is an image of bird on a branch, which our guide told us represents death. Next to it is a symbol that I didn't recognize, and star sits beneath the branch on which the bird is perched. The star represents the good or the divine, and the strange symbol stands for love and faith. In other words, the wall can be loosely interperated as In the presence of death, love and faith alone are good.

Adjacent to the main room is the salle de St. Hugues which was built in 1645. Commisioned by Hugues Betault, a wealthy bishop, the room catered to the rich who had fallen ill. The walls are covered in dynamic and colorful murals depicting stories and themes from the Bible. Compared to the main room where the poor people went, this much smaller, flashier room devoted to people who could already afford private healthcare spits in the face of the Hospital’s original goal. In this way the hospital embodies the contrary nature that often characterizes the Catholic Church. One room is devoted to charity, kindness, and helping the community. The other room is a manifestation of opulence, exclusivity, and wasted resources.

|

| Murals in St. Hugues' room. |

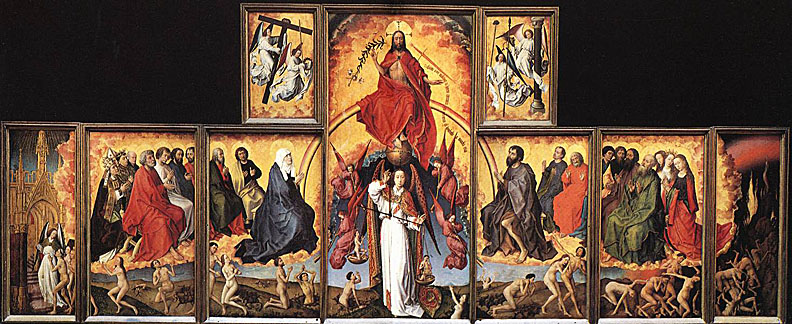

The final room I visited in the hospital housed the original version of Rogier van der Wayden's "The Last Judgement." Different sections of the painting are opened and closed depending on the time in the church calendar. It shows the dead rising and being judged by St. Michael, whose face is disinterested and impartial. The good go off to the left into the shining gates of heaven. The evil go off to the right into fire.

The people who live in Burgundy accept their buildings, art, and attitude as a way of life. The same could be said for Americans as well. I make no value judgments on either attitude; I'm well aware that they both have their shortcomings and their merits. Instead, I wish to express how the attitude of a people can seep even into the buildings in which they live.

No comments:

Post a Comment